Poetry

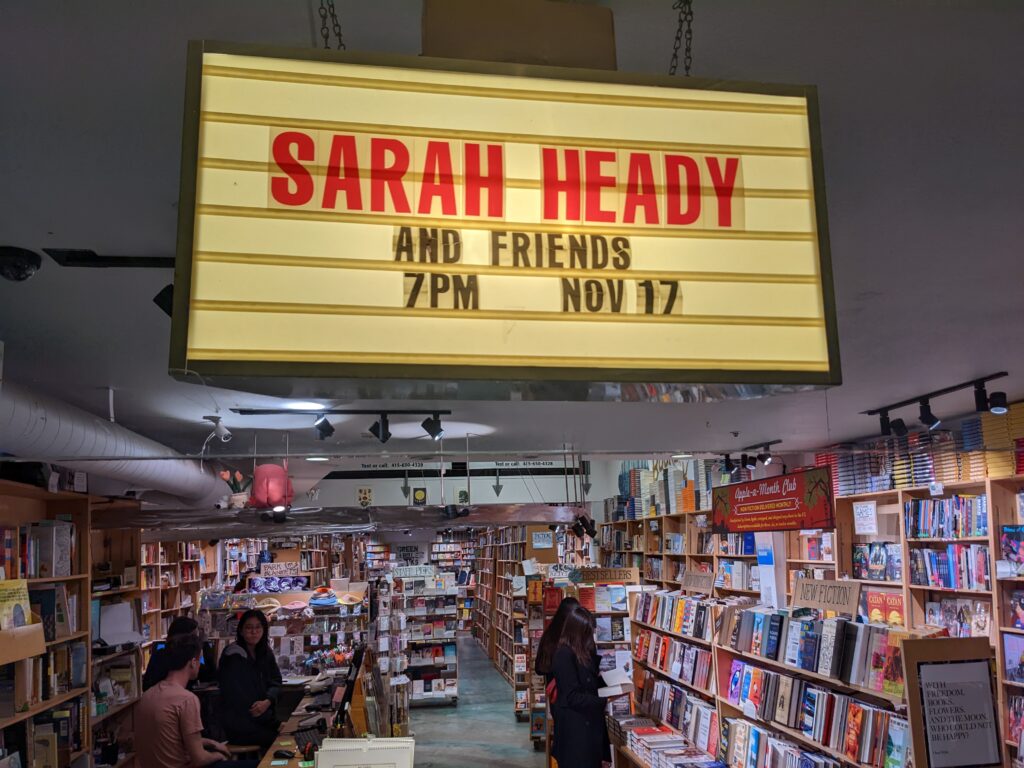

Reading to celebrate COMFORT, Sarah Heady’s new book of poems from Spuyten Duyvil

What a pleasure it was to read at the release reading of COMFORT, a new book of poems by my friend and DropLeaf co-founder Sarah Heady. Kar Johnson over at Green Apple Books on the Park coordinated a lovely IRL/online event, which featured Tanya Holtland reading from her beautiful eco-poetry collection REQUISITE (Platypus Press), Maia Ipp reading an excerpt of SUGARTRUCK, her novel in progress, and Laura Walker reading from PSALMBOOK (Apogee).

COMFORT is a really lovely work, a rich woven thing. Part Midwestern prairie missive, part found-language assemblage, it grapples with domestic labor, woman’s work, prophecy, property, and the land. Sarah Heady has a wondrous way with source materials, weaving history and presence together in lyrical lists and verses.

I read from my long poem, BOOK OF SYBIL (Gorilla Press). Here is what I said to introduce that work, which is now almost 10 years old:

I was in my mid twenties, newly married, and struggling with what it meant to be a wife in a hetero relationship in a patriarchy. Somehow I got drawn into research about the sibyl of ancient Greece and Rome.

I learned that Sibyl was a title given to prophetesses, women who worked in religious centers which traded in prophecy. The most famous Sibyl was the Cumaean Sibyl, though there were many Sibyls operating throughout the ancient world, consulting on affairs of state, serving kings, the nobility, and anyone else who came to them seeking to know the future.

The name Sibyl has a long etymological lineage tying it back to the Magna Mater Great Mother figure, Cybele (SAI-bel), or Kubileya, who originated in Anatolia, or present-day Turkey, but whose cult spread into ancient Greece and later to the court at Rome, where the Great Mother was called upon as a key religious ally to the Roman military.

The Sibyl served the authorities as a mouthpiece, with prophecy justifying present actions, but she also held an ideological status as a divine speaker, someone whose truth was considered unassailable, even by kings. She was a noise maker, in that meaning had to be derived from her torrent of words. Her authority was repeatedly coopted for political gain.

There is a real Book of Sibyl, a set of nine books actually, which is referred to by the historian Lactantius. But we have no remaining primary source for that work. There is another book known as the Sibylline Oracles which was written centuries after the time of the Sibyls but was passed off through the Middle Ages as an ancient document. This book was written as a series of prophecies predicting the rise of Christianity and connected the old cult of the Great Mother with the new Christian framework of Mother and Son. So this chapbook is an attempt to form meaning from all this noise, all these conflicting origins and texts, which have gender and power at their core.

Many thanks to dear friends who attended IRL and online, including my aunt Kathryn Ma, whose new novel THE CHINESE GROOVE is coming out in early 2023.

Two reviews in JERRY Issue #8

A couple reviews of books of poetry — Robin Clarke’s Lines the Quarry (Omnidawn) and Sarah Heady’s Niagara Transnational (14Hills Press) — have been published in the eight issue of JERRY Magazine.

It was a pleasure to read and write about these first books by two devoted and deeply observant poets.

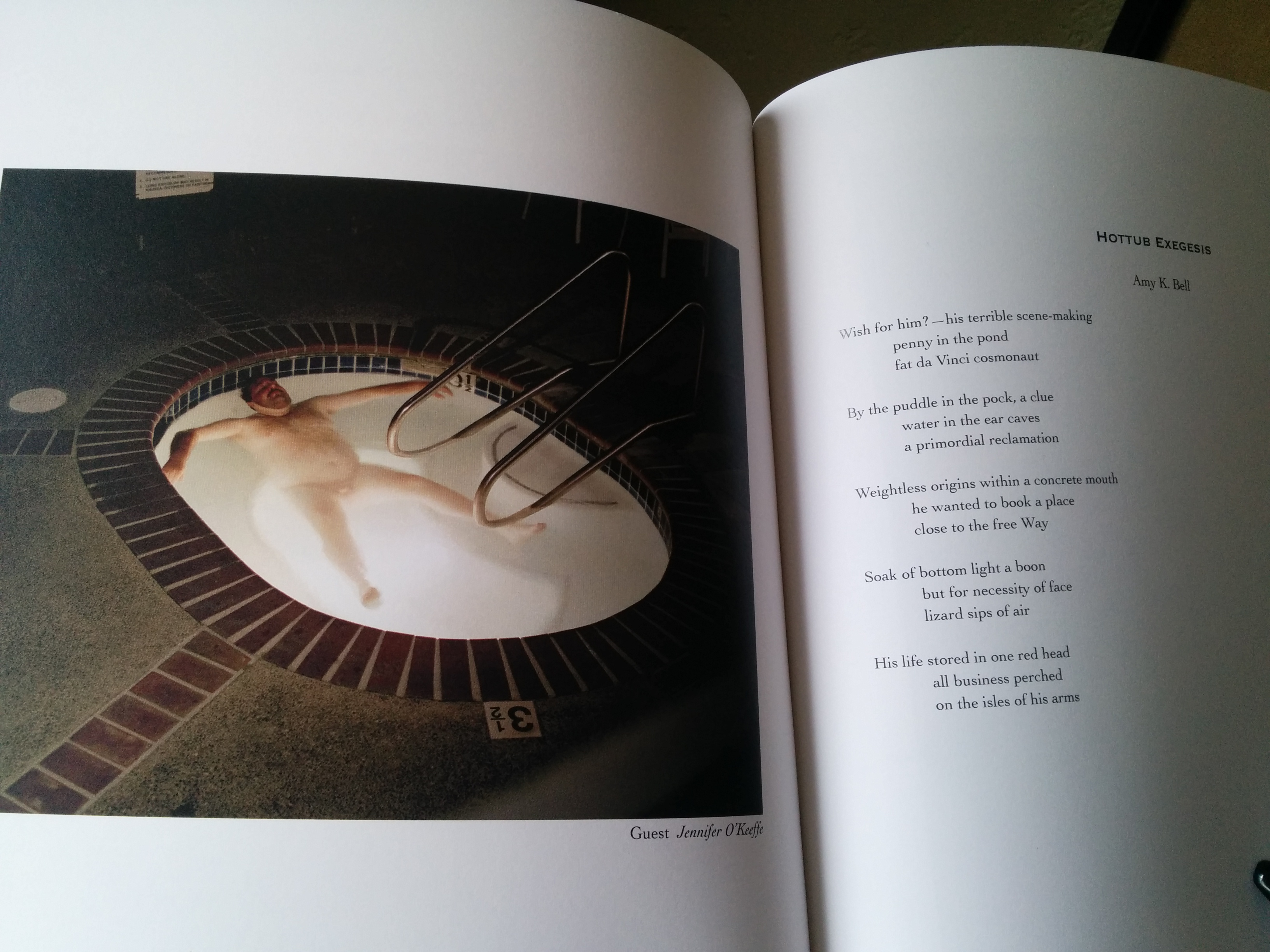

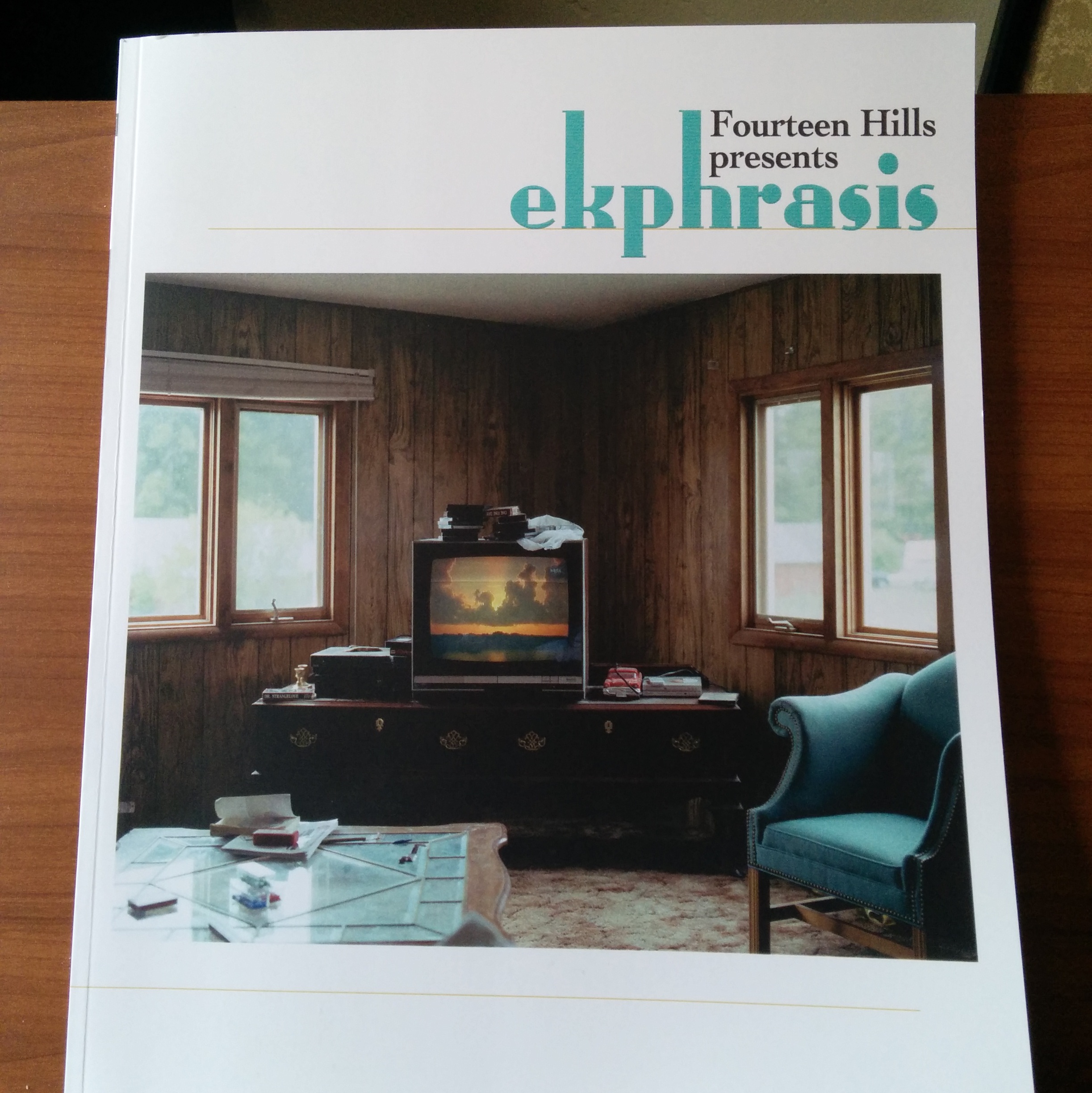

First issue of ‘Ekphrasis’

This Spring, I contributed a poem to a great new publication, Ekphrasis, edited by Monique Mero-Williams and produced by Fourteen Hills and Voices/Visions. I was assigned an image (“Guest” by Jennifer O’Keeffe) and asked to respond. I wrote “Hottub Exegesis”. It is a lovely journal, with nice heft in the hands, and I hope they make many more of them.

Must Be Spoken – an audio poem

The Fetish is Everywhere

Today, a girl in a white dress missed her bus.

She ran to catch it, crowded though it was

—I am not one, well, I haven’t, her thighs.

Ay, this Lolita look is all the rage.

She ran to catch the crowded city bus,

I stepped aside, to let her pass me by—

Ay, this Lolita look is all the rage.

How she pounded, pounded on the gliding door.

I stepped aside to let her pass me by,

From the cypress came a falcon, leaden winged,

How she pounded alongside the gliding door,

I saw the bird’s black head, its heavy dash.

From a cypress came the falcon, leaden winged

To the median of this busy four-lane street.

I saw the bird’s black head, its heavy dash,

It ate from off its talons an impaled thing.

In the median of this busy four-lane street,

I watched the falcon eat around its toe,

It ate from off its talons an impaled thing,

The girl in the white dress had missed the bus.

I watched the falcon eat around its toe,

Her dress was also there, also the rage,

The girl in the white dress, her legs, the chase—

I can’t decide the meaning of it: “slayed”.

Her dress was also there, also the rage,

The falcon flew directly to the sea,

The girl in the white dress sat on the bench

And I was left, to hold the bird with me.

I step outside shaped like a rune

I step outside shaped like a rune, my hands up to feel for the sun’s rays and legs bent to scuttle away, to jump back inside my home if need be. If need be I can insulate myself from the weather, the endless weather, and be the same. The sane same, I can be. Today I am shaped like a rune, I’m curious and translatable, the sun touches all. I step outside and then I’m like a battery, my skin charges, two bars, three bars, four, and I’m warm. I’ll carry it away, away inside and in the car, my skin holds the sun. Bursts and waves, the sun. Radiated and clean, my skin. Caressed and beaten, throughout the day, the sun on me. Day of Radiance on the radio.

I step outside shaped like a peg, my arms at my sides, like a Donii, a woman-peg, laden with flesh and bouncing lightly. Bouncing lightly, the sun off the moon, and back onto the grass, into which I root myself. I point down and then all around, I write light to a camera. I am shaped like a peg, I’m unified and useful, the moon is enough in its changes. Just half, just a sip of moon, it’s enough, only leave me desiring.

I step outside and I roam, I’m off from the jamb-go and all the insulation of the house is packed onto my prudish body. I am off, turned on, I look through a visor made of packing tape, at the world or the new walls. Dense grasses and egret limbs overtake me. I have scared a blue heron and another condor retires. The nettles on the hill pull at my faux fur, the fibers drift up in seed pod smoke. Where there’s only a sheer backing left, the wind of all changes rustles over true skin.

My Sister Down a Green Road

I can see my sister walking down a green road in early spring. The ice is in its first thaw. The trees sway, remembering the breeze. The farmer’s fields beside the road are heavy with clodded loam and aching rotted twigs. Black birds flap chilled mist from their wings and swoop.

She is walking down that road, the fingers of one hand flared in the direction of the the moss. She is lumbering; her one foot turns inward with each step. Her head is foremost, propelled by an unwomanly hunch. Loose strands of hair caress her cheek and slap the collar of her jacket.

I can see her on this road, how others might see her. Her fairness encouraged by the fair wind, the heat of her and the cool of all forming their ruddy rouge, the unwanted sign. She holds back a tide with that brave hunch. Her dark eyes are stones, old and everywhere, unbefitting the sweet face.

I can see her walking down a green road, crouched from where I am, inside her pocket. Her fist is here with me, in the pocket. Her thumb is chewed and cracked – Beauty’s surprise. I study the pulse at her wrist, even, and test the clench of her fingers, odd.

The green road is a pile behind us. Past the lining of her pocket, past the sockets of my eyes.

Phone

Hank Skeels stands at the entrance to Club Throb, the hottest, keeping watch over the VIP guests as they ooze in with perfect timing. The regular guests come wide-eyed as they please and Hank can’t blame them. He bars the inelegant riff-raff, the dirty phoneless.

A step inside the club, Ben leans away from Betty’s gooey lipstick advances as they stride in. She’s already at my neck, Ben says into his phone, which is shaped like a stubby black billy club, or is it a small baseball bat. Betty’s phone is in her clutch purse, a pair of lips wrapped in pink satin, buzzing.

Enter Judy and Jim, strolling, his arm at her back. She swats it away with a glance. I’m on the phone, sweetie, she says, and he removes it. Jim can’t take his eyes off of his wife’s shape in her gown, the way her slender fingers grip the roundness of her armadillo phone, commanding an underling to get it out by tomorrow latest. He left his fork phone at home, charging.

The young actress-waitress, daughter of the club owner’s brother, Shayna holds a tray of champagne glasses and circles the room, smiling with perfect teeth in the roaming laser lights, wishing she could get back into her locker in the employee lounge to peek at her phone, a disco ball.

In the alley behind Club Throb, two men and two women are deep in an angst-ridden discussion about phones in society, a conversation that started when one of the guys Tim mocked Bill’s older model. The two friends had almost come to blows, when the woman Aisha quietly suggests that they smash their phones, right here and now, as an act of self-liberation.

Tim, Bill and Aisha do it; they crack the outer cases under their feet, spreading the remains of a red handkerchief, a blue handkerchief, and a dried flower onto the pavement. They separate the inner motherboard from its wires with their heels. Silicone and bits of glass ground into the grime of the pavement make them feel wild, accomplished, for a moment. A thread of loneliness tightens. They watch mutely as Bill struggles to light the blue curlicue cord on fire, a wet fuse of a bomb. The remaining friend, the one who couldn’t smash her phone, Aparna, jogs to catch the bus. Her hands grip tightly inside her pocket around her phone, which is a tin of mints.

The Anderson family – Mom, Dad, Penny, Michael, and baby Alex – stand in a group within the main crowd of guests by the podium, waiting patiently, each holding green pear phones. Penny and Michael are embarrassed to be seen with their parents, who are underdressed. This place is packed, Penny whispers. Michael holds his phone like a platter to his chin, in loudspeaker mode, and says, I think they’re about to get started. Mom texts Dad about Penny’s weight problem. Dad tells her not to worry, in so many words. Baby Alex is in Mom’s arms, her phone covered in slobber.

The beautiful and normal-looking people have all gathered by 10pm, when Hank Skeels hears his boss speak into the phone in his ear, Close the doors, it’s starting.

A cascade of synth bells falls over the eager audience. The dais is positively cinematic, mouths Judy into her armadillo. A large platform, its floor painted in thick black and white stripes and covered to extravagance by a mound of dark red roses. A black velvet cloth has been draped over a glass case that sits atop the flower mound.

That is it, the thing we’ve all been invited to see.

The percolating silence is deafening, maddening, here’s everyone’s attention. They set their phones in camera mode, fingers hovering over the button.

Hank Skeels takes the stage, hands clasped together in front of him, and looks over the crowd. They think he might speak but he does not.

Taking her cue from the silence, the model, Po, emerges from the employee lounge. She is naked, her body painted entirely silver, up to her hairlines. Her nails and lips are a lush red. Shayna, standing in the hallway, gasps when she sees her.

Po enters the main area. Her gait is slow. Slow-motion bullet of a woman. I am a juggernaut, she thinks to herself. Slow, but lacking any inertia.

Po ascends the dais on black and white steps. She turns to face the audience, orienting herself to the street outside, the city beyond, as the boss has instructed her to do in his superstition. She bows to them.

Everyone bows back, even Mom and Dad, though it is not their custom.

Po takes three steps backwards to stand beside the covered case. She lifts her silver arm and places her hand on the black velvet. In a slash, she whips the cloth away. The lights swirl and land on the case upon the dais.

It is a new phone.

Its body is chrome silver and gleaming with a dark radiance, like mercury, molten in the lights. It is wider at the base, then narrows into a soft point. A bullet.

Loud clicks of photographs being taken.

The light of individual phones pulled from above the heads of the crowd, down to the chest, dispersed in messages, reaching out to the other side of earth.

Hank Skeels stares at the bullet, motionless. I believe you’re in love, Hank.

Mother’s Day Poem

While I stood trimming

The little pale pink roses

I noticed some blossoms

Had new green buds

Poised & ready in their centers

Like girls who emerge

Wearing the manes of their mothers.